HTTP

Introduction

HTTP is the cornerstone of the web ecosystem, providing the foundation for exchanging data and enabling various types of internet services. It has gone through several evolutions especially in the last few years with the introduction of HTTP/2 and, more recently, HTTP/3. HTTP/2 attempted to address shortcomings of HTTP/1.1 such as the limited number of concurrent requests. At first glance, HTTP/3 is similar to HTTP/2 as the semantics are the same, but under the hood HTTP/3 is radically different from its predecessors in that it utilizes QUIC as the transport protocol instead of TCP.

As HTTP/2 provides the basis for HTTP/3, we analyze key features of HTTP/2 such as HTTP/2 Push, prioritization, and multiplexing to understand how much they are still used. We also present case studies from various deployment experiences of these features. For example, HTTP/2 Push allows web servers to preemptively send the response of a resource before the client requests it.

While both push and prioritization should theoretically be beneficial to end users, they can be challenging to use. We discuss new technologies that can potentially be used as alternatives to underperforming HTTP/2 features. For example, 103 Early Hints responses provides an alternative to HTTP/2 server push that achieves the same performance goal of preemptive resource fetches.

Finally, we dive into HTTP/3 by discussing how it is an improvement over HTTP/2 and by analyzing the current support for HTTP/3, where we observe some increase from 2021. We hope that the data points provided in this chapter will provide some insights on future trends and pointers to new technologies that developers can experiment with to improve user experiences.

Evolution of HTTP

HTTP is one of the most important Internet protocols because it powers communications for the web. It began as a text-based protocol through the first three versions: 0.9, 1.0, and 1.1. With its extensibility, HTTP/1.1 was the current HTTP version for 15 years until 2015.

HTTP/2 was a major milestone of HTTP as it evolved from a text-based protocol to a binary-based one. Where HTTP/1.1 supports only serial request and response exchanges, HTTP/2 supports concurrency. Clients and servers represent requests and responses as streams of binary frames. Streams have unique identifiers, which allows frames to be multiplexed and interleaved.

The latest version of HTTP is HTTP/3, which was recently standardized by the IETF in June 2022. While HTTP/3 implements the same features as HTTP/2, there is a vital difference in how it is transported across the internet. HTTP/3 is built on top of QUIC, a UDP-based protocol, which alleviates some of the performance issues that HTTP/2 can face on a lossy network.

HTTP/2 adoption

With various HTTP versions introduced over the years, we begin by describing the current state of HTTP version adoption. We measure the HTTP version usage by taking all resources in the 2022 Web Almanac dataset and identify which version of HTTP each resource was served on.

However, with our setup, it is not trivial to accurately count resources delivered on HTTP/3, as clients have to discover HTTP/3 support, typically via the alt-svc HTTP response header. By the time the client receives the alt-svc header however, it has already completed the protocol negotiation for HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/2. Only after this point can the client upgrade the protocol to HTTP/3 on subsequent requests or page loads. As such, our data never captures a full HTTP/3 page load.

With the discovery of HTTP/3 being so delayed via the alt-svc HTTP header mechanism, our measurements may undercount resources that would have been delivered on HTTP/3 for normal browsing users. Thus, we group resources delivered on HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 together as HTTP/2+.

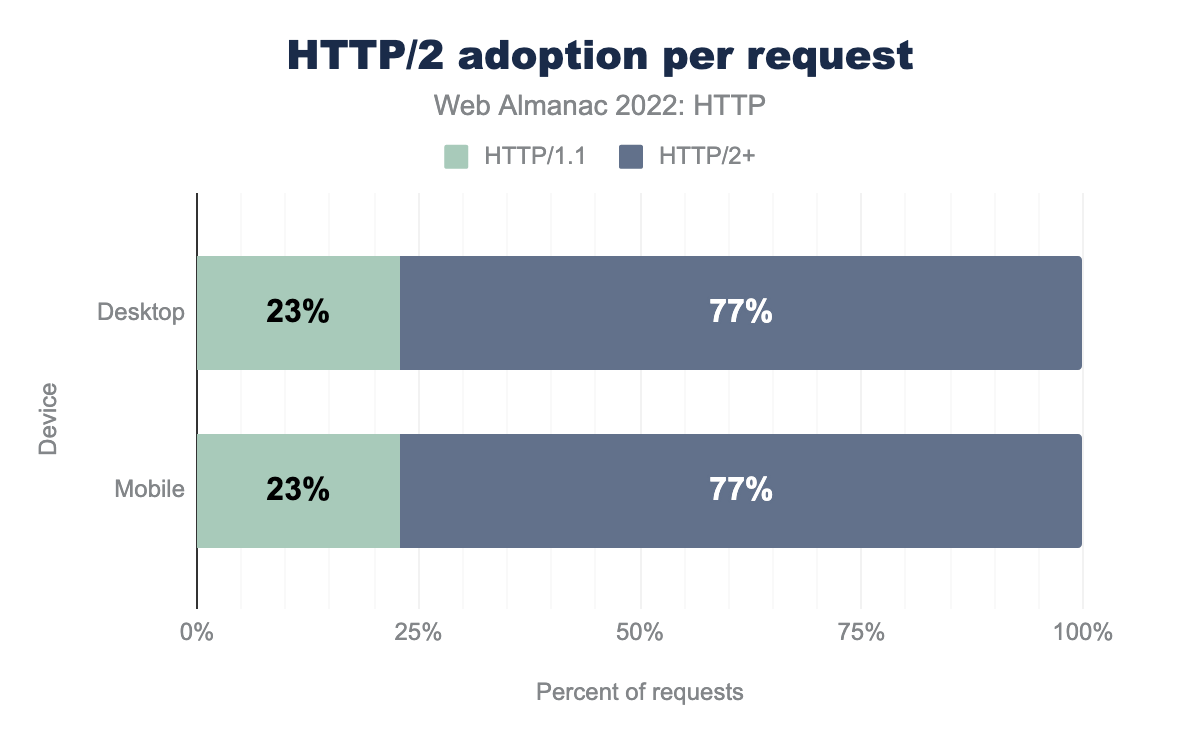

First, to understand the status quo, we measure the prevalence of HTTP/2+ adoption. In June 2022, we observed that roughly 77% of requests from our loads use HTTP/2+. This is a 5% increase in HTTP/2+ adoption from July 2021, where we observed that 73% of the requests were on HTTP/2+.

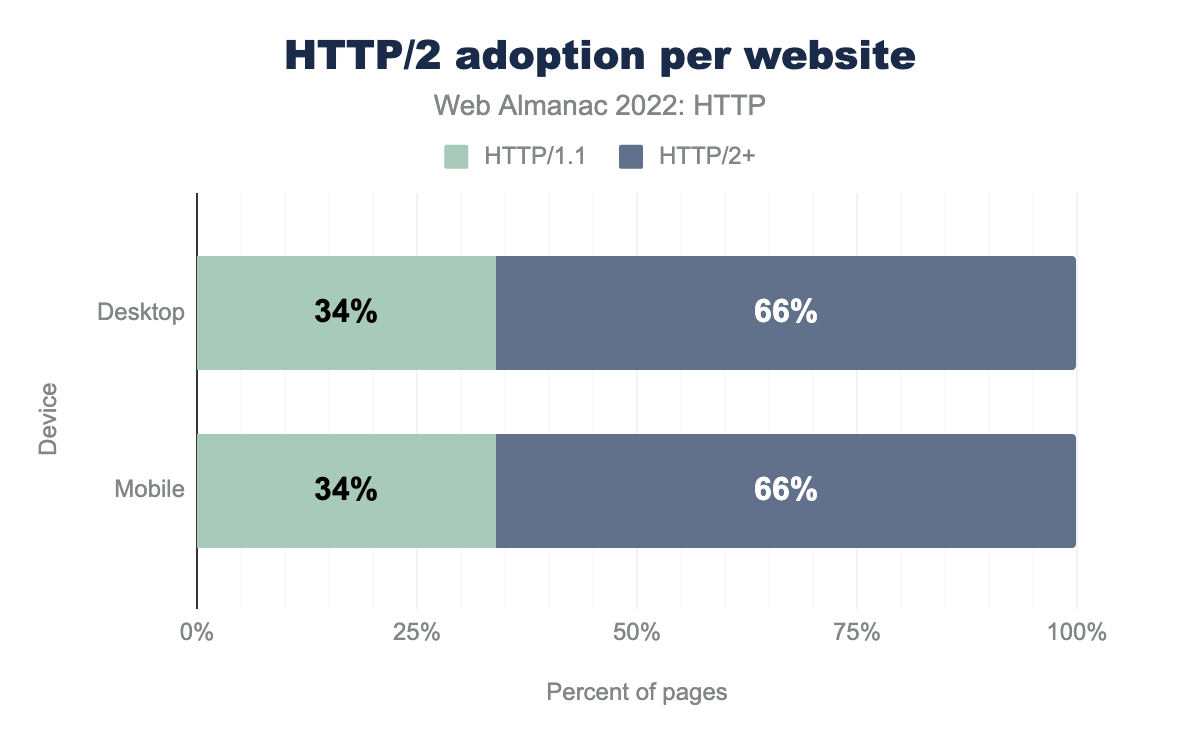

With the increase in HTTP/2+ adoption, we would like to understand the driving forces that enable the increase. First, we analyze the HTTP/2+ adoption at per-website granularity by checking whether the landing page of the website was served on HTTP/2+. We observed that approximately 66% of the websites from our dataset, on both desktop and mobile settings, were served on HTTP/2+, whereas this was only true for approximately 60% of the websites in our dataset in 2021. This increase is a positive trend which suggests that websites are ready and moving towards an up-to-date version of HTTP.

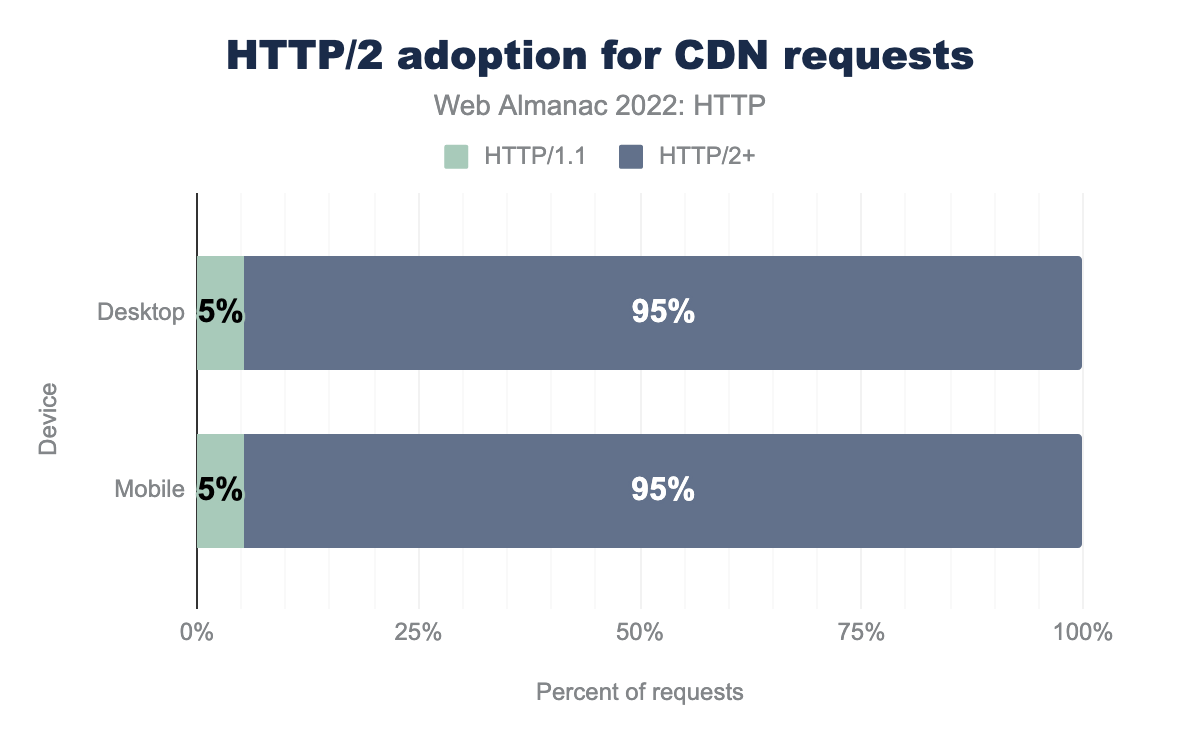

Another factor in enabling HTTP/2+ adoption is resources served from CDN. Similar to the observation in our 2021 analysis, we noticed that most resources served from a CDN were on HTTP/2+. The figure above shows that 95% of the requests served from CDN were delivered on HTTP/2+.

Benefits of HTTP/2 and HTTP/3

Next, we focus on how features that HTTP/2 introduced are being adopted. We primarily focus on three notable concepts: multiplexing requests over a single network connection, resource prioritization, and HTTP/2 Push.

Multiplexing requests over a single connection

An important feature of HTTP/2 is multiplexing requests over a single TCP connection. This is a substantial improvement to earlier versions of HTTP where only one concurrent request is allowed on a TCP connection and, in most cases, only six parallel TCP connections are allowed to a hostname. HTTP/2 introduces the concept of a stream; a logical representation of a connection that is used for resource delivery. Multiple HTTP/2 streams can then be multiplexed onto a single TCP connection thereby removing the per-connection concurrency limitations.

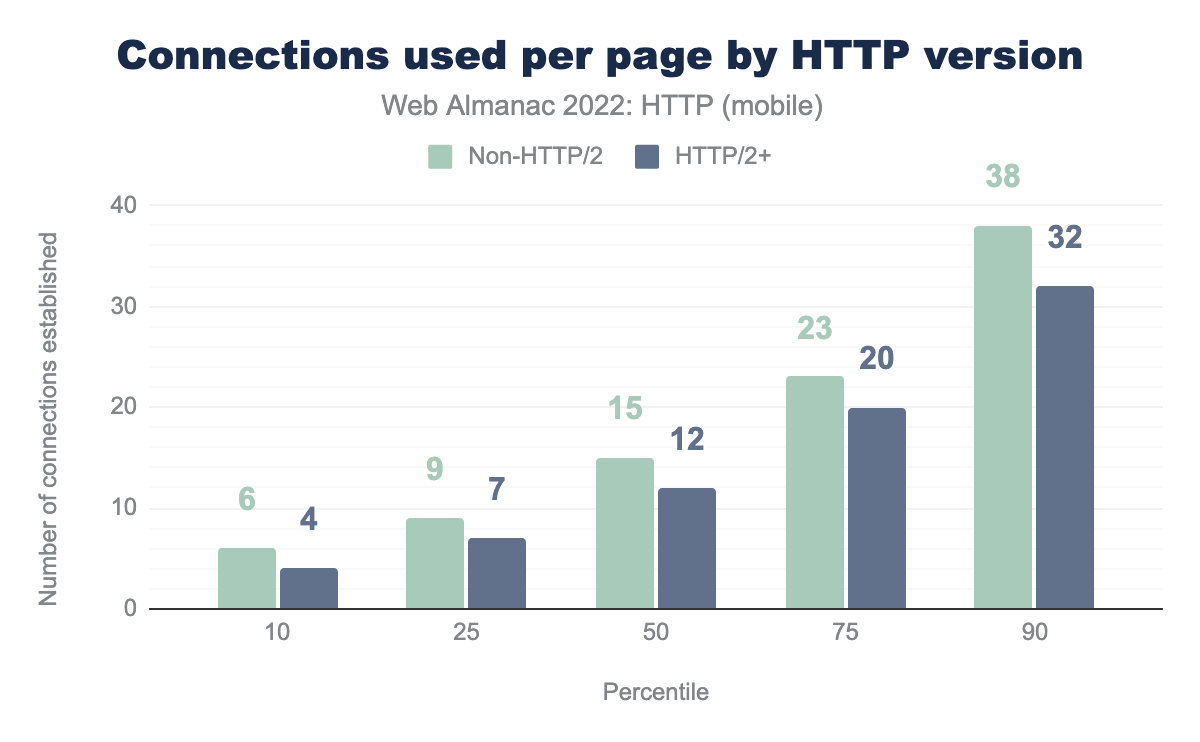

An implication of multiplexing requests into one TCP connection is the reduction of connections required during page loads. Similar to our findings in 2021, pages with HTTP/2 enabled we observe fewer connections than pages that do not have HTTP/2 enabled.

The figure above shows that the median mobile page has 12 connections established during the page load when HTTP/2 is enabled. In contrast, the median page without HTTP/2 has 15 connections established—an overhead of 3 additional connections. However, the overhead worsens at higher percentiles. The page at the 90th percentile with HTTP/2 enabled has 32 connections, whereas the 90th percentile page without HTTP/2 enabled has 38 connections—a 6 additional connection overhead. These trends are the same between desktop and mobile versions of websites.

Given that we observe an increase in HTTP/2 adoption over the year, it is unsurprising that the number of TCP connections overall has been gradually decreasing over the years. A longitudinal view from HTTP Archive shows that the median number of connections established decreased by 9 connections, from 22 connections in 2017 to 13 connections in 2022.

Resource prioritization

With HTTP/2, clients can multiplex multiple requests on the same connection. An implication is that this can negatively impact delivery of render-blocking resources if many resources are inflight at the same time. This can lead to poor user experience. In its original standard, HTTP/2 attempts to address this by proposing a priority tree that clients construct during page load and which web servers can use to prioritize sending more important responses. However, this approach is difficult to use and many web servers and CDNs either did not correctly implement it or ignored it. Because of this, it was suggested in a later iteration of HTTP/2 that a different scheme should be used.

With the challenges to HTTP/2 priorities, a new prioritization scheme was needed. The Extensible Prioritization Scheme for HTTP was developed separately from HTTP/3 and was standardized in June 2022. In this scheme, clients can explicitly assign a priority composed of two parameters via the priority HTTP header or the PRIORITY_UPDATE frame. The first parameter, urgency, tells the server the priority of the requested resource. The second parameter, incremental, tells the server whether a resource can be partially used at the client (for example, partially displaying an image as parts of it arrive). Defining the scheme as a HTTP header and as the PRIORITY_UPDATE frame makes it extensible as both formats were designed to provide future extensibility. At the time of writing, the scheme has been deployed for HTTP/3 in Safari, Firefox, and Chrome.

While most of the resource priorities are decided by the browser itself, developers can now also use the new priority hints to tweak the priority of a particular resource. Priority hints can be specified via the fetchpriority attribute in the HTML. For example, suppose that a website would like to prioritize a hero image, it can add fetchpriority to the image tag:

<img src="hero.png" fetchpriority="high">Priority hints can be very effective in improving user experience. For example, Etsy conducted an experiment and observed a 4% improvement in Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) on product listing pages that included priority hints for certain images.

While Priority Hints was only recently released at the end of April 2022 as part of Chrome 101, it has a very promising adoption as we observe that approximately 1% of desktop web pages and 1.2% of mobile web pages have already adopted priority hints in August 2022. With its potential to improve user experience with relative ease, it may be a good feature to experiment with.

HTTP/2 Push

HTTP/2 Push allows web servers to pre-emptively send a response to a request before that request is even sent by the client. For example, a website provider can push a resource that will be used during a page load to the end user along with the main HTML.

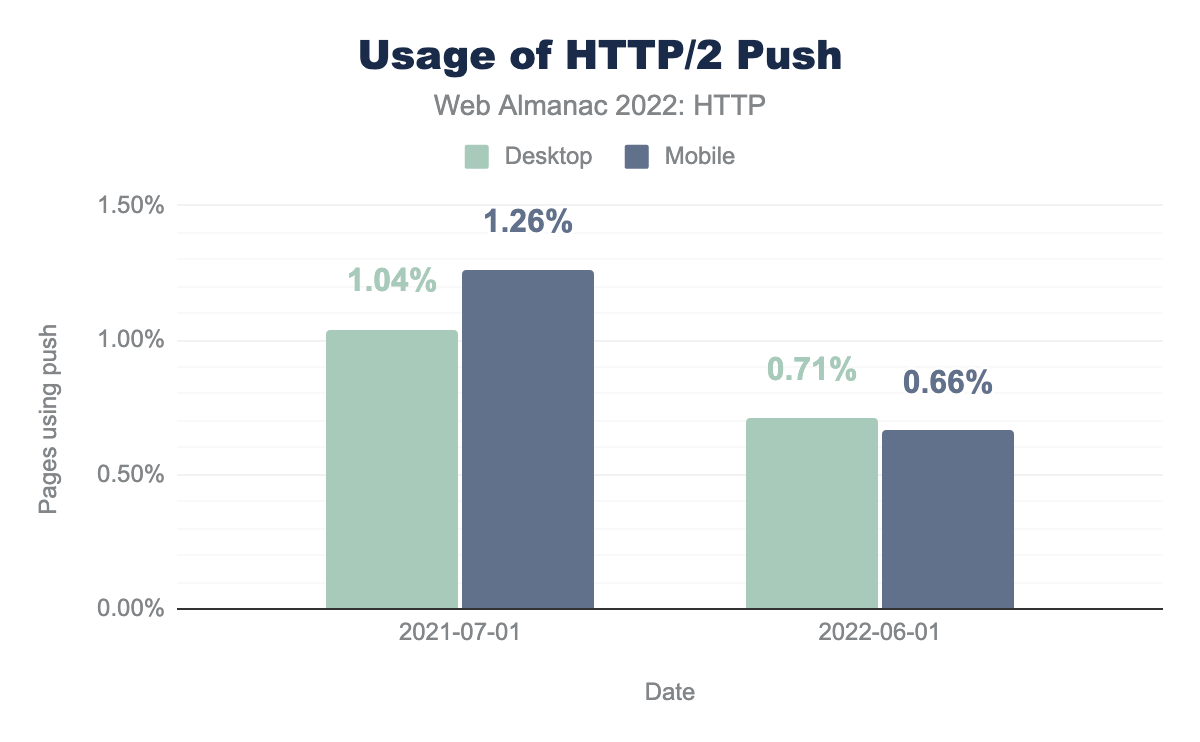

In 2021, as shown in the figure above, the percentage of websites using push was very low at 1.26% for mobile. However, in this year’s analysis, the number of websites using push decreases to 0.66% for mobile websites. This marks the first decrease in push usage since 2020.

The decrease in websites using push is likely because it is difficult to use effectively. For example, websites cannot accurately know whether a resource being pushed already exists in the client’s cache. If it is in the client’s cache, the bandwidth used for pushing the resource is wasteful.

With the difficulties, Chrome decided to deprecate HTTP/2 Push starting from Chrome version 106. Despite push officially still being a part of the HTTP/3 standard, Chrome—which the HTTP Archive crawler uses—never implemented push for HTTP/3 connections, which might further explain the reduction in usage as sites moved to that version and lost the ability to push.

Alternatives to HTTP/2 Push

Given the challenges to using HTTP/2 Push, and it’s deprecation from Chrome, developers may be wondering about alternatives.

Preload

Developers can use Preload as one alternative to pre-emptively request a resource that will be used later in a page load. This is enabled by including<link rel="preload"> in the <head> section of the HTML. For example:

<link rel="preload" href="/css/style.css" as="style">Or as a Link HTTP header:

Link: </css/style.css>; rel="preload"; as="style"Either option allows web servers to include additional URLs or important resources. The client can then issue requests for the provided URLs before the resources are normally discovered during the page load.

While not quite as fast as proactively pushing resources, this is a lot safer in allowing the browser to choose whether to fetch those resources or not if—for example—it already has a copy in the cache.

<link rel="preload">.

We observed a large number of pages in our dataset include a <link rel="preload"> tag—approximately 25% on both desktop and mobile.

103 Early Hints

In 2017, the 103 Early Hints status code was proposed and Chrome added support for it this year.

Early Hints can be used to send interim HTTP responses before the final response of the requested object. They can boost performance by leveraging the fact that web servers often require some time to prepare a response, especially for the main HTML document if it is dynamically rendered.

One use case of Early Hints is to deliver Link: rel="preload" for resources to preemptively fetch, or Link: rel="preconnect" to preemptively connect to other domains. Other headers can conceptually also be conveyed, though this is not supported by any browser.

Early hints can be a better alternative than push because clients retain greater control over how the resources are fetched, but still allow an improvement on just adding preloads and preconnects to the main document HTML. Furthermore, Early Hints can potentially be used for 3rd party resources, which was not possible with push, though again this is not yet supported on any browser.

There are studies showing that adopting Early Hints can improve user experience. For example, Shopify observed 20-30% LCP improvements in their lab study. We observe that approximately 1.6% of websites in our dataset have adopted Early Hints even at this early stage and most of the adoption (1.5%) stems from websites running on Shopify’s platform.

With the 25% of websites including <link rel="preload"> with the page response, there is significant potential to convert such link nodes to Early Hints.

HTTP/3

In the remainder of this section, we turn our focus to HTTP/3, as it is the future of HTTP and was standardized in June 2022. In particular, we explore the improvements of HTTP/3 over its predecessors and how much support it currently has. For a more detailed explanation on HTTP/3, you can refer to this excellent series of posts from Robin Marx, who also helped review this chapter.

Benefits of HTTP/3

While HTTP/2 introduced various improvements over its predecessor, there remain further challenges and opportunities for the protocol. For example, even though multiplexing of requests onto a single TCP connection alleviated head-of-line blocking issues for each request, delivering requests using this method can still be inefficient. This is because lost TCP packets can prevent properly received later TCP packets from being processed until their retransmission arrives—even if the later TCP packet is for a separate HTTP stream. TCP has no concept of the multiplexing happening in the higher, HTTP protocol and so holds up all streams.

HTTP/3 aims to improve upon the shortcomings of HTTP/2 and to do that it is built on QUIC, a UDP-based transport protocol. QUIC addresses TCP head-of-line blocking by implementing reliable packet delivery on top of UDP at a per-stream granularity.

HTTP/3 support

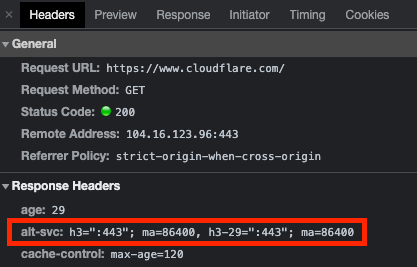

To advertise that HTTP/3 is supported, web servers rely on the alt-svc in the HTTP response header. The value of alt-svc header contains a list of protocols supported by the server.

alt-svc response header supporting HTTP/3 with values h3, and h3-29.alt-svc response header example.

For example, in September 2022, the alt-svc value in the response for https://www.cloudflare.com is h3=":443"; ma=86400, h3-29=":443"; ma=86400 as shown in the screenshot below. h3 and h3-29 tell us that Cloudflare supports HTTP/3 and IETF draft 29 of HTTP/3 over UDP port 443. There is also a proposal to speed up the discovery of HTTP/3 as part of DNS lookup; for more details see this post from Cloudflare.

We analyze HTTP/3 adoption by identifying a resource that was served on HTTP/3 or its response header contained an alt-svc header with either h3 or h3-29 as one of the protocols advertised. This allows us to understand if HTTP/3 could be used, and ignores the limitations mentioned above, of the fresh instance run by our crawler, which has yet to see the alt-svc header.

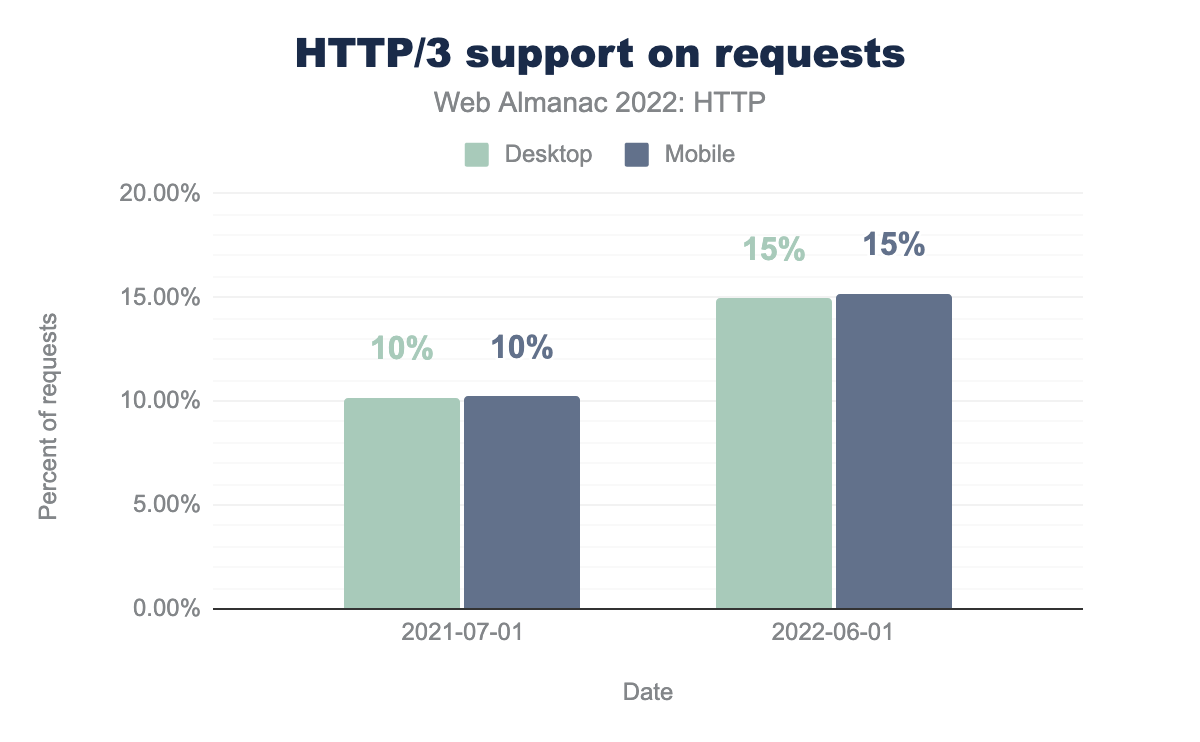

The figure above shows that there is a 5 percentage point increase, from 10% to 15%, in the percentage of requests with HTTP/3 support since last year’s Web Almanac. The same increase was observed on both desktop and mobile requests.

Similar to HTTP/2+ adoption, most of the HTTP/3 support originates from CDNs. We expect the support to grow in the future when more CDNs start to support HTTP/3.

Conclusion

This past year was an eventful year for the HTTP protocol especially with HTTP/3 being standardized. We continue to observe high HTTP/2 utilization and see a strong upcoming HTTP/3 support from web servers.

In addition, we have seen strong growth in the ecosystem for technologies that address some of the critical challenges in HTTP/2. 103 Early Hints provides a safer alternative for Server Push and its client support has taken a large step forward with Chrome now supporting it. A new standard for HTTP Prioritization was finalized; major browsers and some web servers already support it for HTTP/3. Furthermore, Priority Hints was added to the web platform to allow clients to further refine prioritization on both HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 and early experiments have yielded promising user experience improvements.

This is an exciting time going forward for the HTTP protocol and the web ecosystem. We are excited to see how these new technologies will get adopted and what effects they will have on user experience.